Paramount Records

World Music Foundation Podcast | Season 1, Episode 2

“They say Delta Blues is the roots, and everything else is the fruits.”

About this Episode

Our second episode brings us to a small town in the Northern part of the U.S. where we, surprisingly, find a deep Blues history. We follow Paramount Records through the peak of success, recording landmark artists that changed Western popular music forever, but this music, at several times, was almost lost forever. We follow the thin thread of events and recent efforts that have gone into preserving this important musical history.

John Gardner: Hello, Hello and welcome again to the World Music Foundation podcast. I’m your host, John Gardner and today we speak about an important part of American music history. That was nearly lost.

(Music)

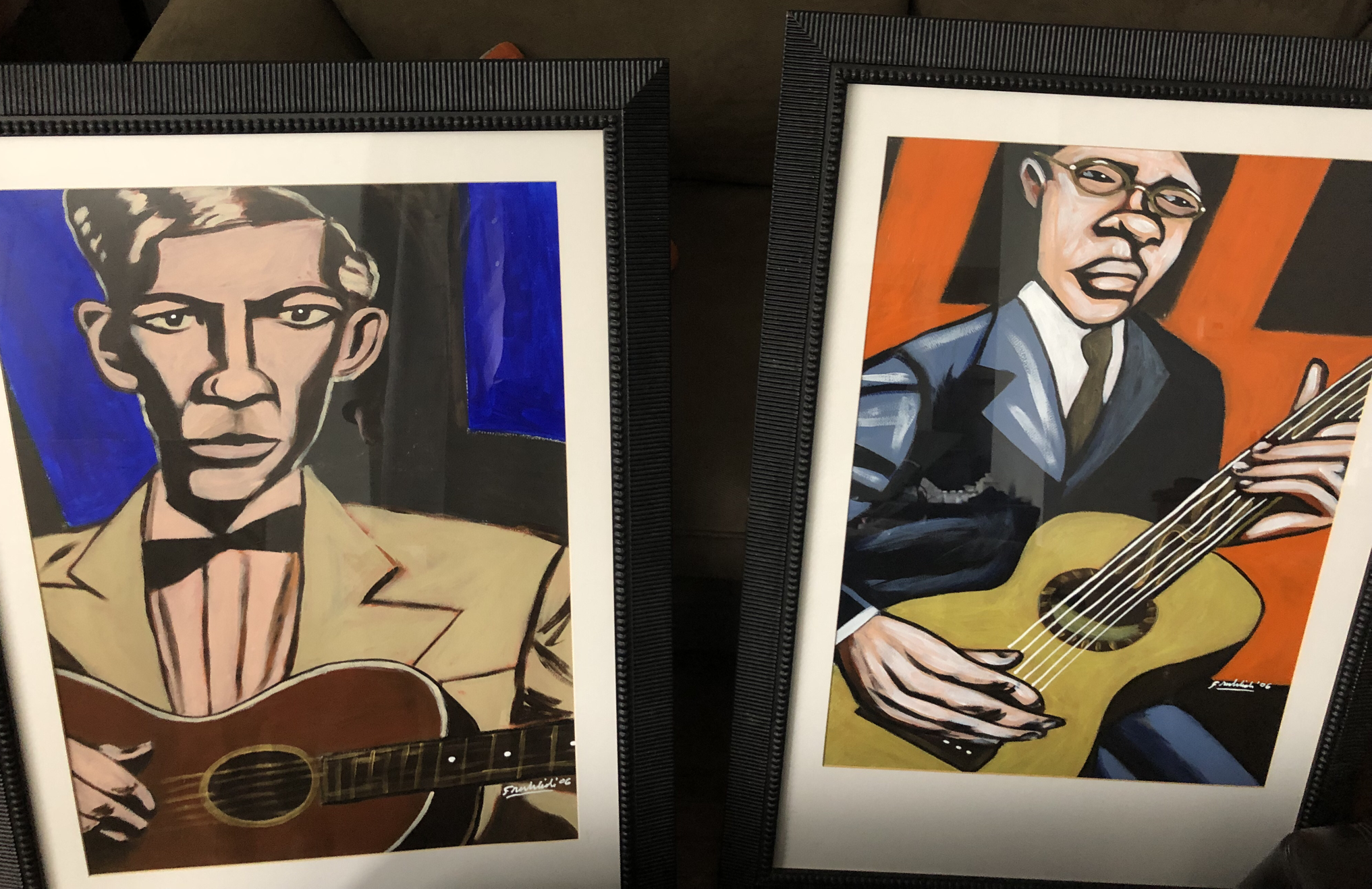

Well, the inspiration for today’s episode actually came from my personal life. I was up in Wisconsin just a handful of weekends ago, and I was in a resale shop. And I saw hanging there three fairly amazing original paintings of hard core bluesmen. Now these weren’t your more mainstream or widely well known artists like Muddy Waters or B.B King. We’re talking some pretty deep cuts Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charlie Patton, Skip James and the reason it stood out to me as surprising or unexpected, is if you’re not familiar with the United States, Wisconsin is a very northern state. So the blues, of course, if you trace it back far enough goes back to Africa.

But the blues as we know it, we would say, originated in the southern states of the United States. So Mississippi, Texas, that kind of thing. It came from the plantations very deeply rooted African American history. Now Wisconsin is about as far from that as you can possibly get. It runs about 85% white. It’s just so far from the environment that created the blues, so that kind of got my attention. I thought it was interesting, but mainly I just needed to buy those paintings. I got two of them. I’d couldn’t find room for Skip James. Sorry, but the other two are hanging in my hallway here, but I didn’t think too much of it until the next day. The next day it was a pretty musical weekend. I was at a screening of a documentary on Big Bill Broonzy.

It was called Big Bill Broonzy, The Man Who Brought The Blues to Europe. And in that documentary they mentioned that he had recorded for Paramount Records. Well, not too surprising. As a fan of the blues, I realized almost anyone who was anyone in the early 19 hundreds recorded for Paramount Records, but specifically they mentioned that he went up to graft in Wisconsin to record for Paramount records.It was like Hold on that That might be the reason. So start researching and turns out these paintings are directly connected to the Paramount Records, and they’re actually symbols of the efforts has gone into reclaiming that history and preserving it.But before we get into how it’s being recovered first, what is this history?What is the importance of Paramount records? So let’s take you back there.

(Music)

The year 1917 has a good place to start as any. The first World War had been raging for several years at this point, and that’s important because when the US joined the war against Germany and Austria, Hungary, overseas Americans faced a conflict of musical interest at home. Classical music was already waning and popularity because of a new and exciting genre called Jazz. But think about it, this terrible bloody wars, raging friends of family or being killed over there fighting against Germany and Austria. Who we gonna pop on the phonograph to unwind, too? Bach, Beethoven, Brahms. They’re German. Hidden Mueller Mozart? They’re Austrian. So American audiences turned to more homegrown styles of music like Vaudevillian performers and Dixieland Jazz. And even Creole became the rage in many urban environments. And then there were Military Bands.

Maybe it was the war time nationalism, but some of these military bands that began to be nationally celebrated, were actually led by people of color. Those military bands might be the first time the American public began to see past skin color in order to hear great music. But also, if you look at it at the same time, some of the top songs in the country were written from the perspective of black people. Now they were being performed by black people. They were in fact being performed by whites. Al Jolson, for example, was the nation’s most popular and highest paid entertainer at the time, and several of his performances were sung in blackface, pretending to be a black man. I guess that was just a little more palpable to a nation still knee deep and flagrant social injustice and racism towards African Americans. But unknowingly, American audiences were getting prime to see and hear African Americans on stage and on recordings. So things were changing. it was very slowly but at least things were changing, but we were the Blues in all this. You know, some of the popular recordings of the day We’re Bluey but it sure wasn’t true Blues.

Blues was in the south and black churches and poverty in black communities struggling with the reality of post Slavery, Jim Crow America. This raw form of black expression. It wasn’t being circulated. It wasn’t being recorded yet. But when people would take notice just a few years later, who would change the face of music internationally and right in the middle of all of it would be a record company in the small town of Grafton, Wisconsin, called Paramount Records.

See in 1917 saw the dawn of Paramount Records and it wasn’t a factory for Pop hit records as we might imagine when we picture record company instead, Paramount was quite literally part of a factory, a furniture factory. In fact, it wasn’t records that they were interested in selling at all. It was record players, you know. Actually, at the time it was phonographs. They were a part of the Wisconsin Chair Company, which was founded back in the 1800s. But around this time, 1917 they started getting into the business of making phonograph cabinets. So what started as just a means of making a buck peddling phonograph and phonograph cabinets actually becomes very important for music history, because we know from this vantage point that in the end they end up recording some of the most important musicians and music to ever come out of the U. S. But, man, you sure would not have guessed that when they started out, they didn’t know what they were doing. It took one guy to come along later to pretty much saved the whole operation.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: In the beginning, they practically recorded everything for which market was available.

John Gardner: That’s Alex Van Der Tuuk. Basically, there’s not a person alive that knows more about Paramount Records in this guy. He’s the leading authority, literally wrote the book on it: Rise and Fall of Paramount Records.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: In the early days, they recorded mainly marches. They specifically contracted artist that already have been recorded for the past 15 years and were not expensive anymore to contract. So what you see in the first 5 years is recording the song of the day popular, songs, even some Classical Music. They tried without success and then started something that looked like Jazz and then recorded more Vaudeville 10 Show and Music. And then even pre runner of Country music that they went went with wind. Whatever was popular, they record as well.

John Gardner: They’re recording Pray Style is getting them nowhere. They’re actually missing what’s happening right under their noses. All of those cultural factors that we mentioned earlier finally came to a head in 1920 and the first true blues record sung by an African American was widely sold. The singer was Mamie Smith. The track was called Crazy Blues. Now, in the process of selling 75,000 records in its first month alone. Record companies not only saw white audiences purchasing this record, but most importantly, for the first time, the purchasing power of African Americans was observed. This issued in a whole new, important market of music by African Americans for African Americans.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: They had an overall term for that, and they called it race records. Around 1916-17 the African American people referred to themselves as be proud of the race, and then they meant, be proud of your own race. And that’s why companies like Paramount came with specific rennick. It’s aimed to that population, which was 10% of the American people.

John Gardner: So it’s perfect timing only a handful generations removed from slavery. But the African American population in the U. S. has a growing middle class that is now willing and able, excited to start purchasing music made by other African Americans, and the Wisconsin chair company had just newly started this record business. It seems like they’re set up there ready to go. But how in the world of these white guys up in Wisconsin ever going to get plugged in to this exploding market of race music? Well, let me introduce you to who I consider to be the world’s first black record executive, Mayo “Ink” J. Williams.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: Mayo J. Williams opened an office and add these idea, “Why not find a way to record African American artists?” He then approached very bluntly, Paramount and went up to, Ah, Port Washington, knowing that they had tried some trial balloons on Blues music and and he said, Well, I think we should open an office in Chicago. There’s a lot of black musicians there. If we put a sign in the window that we can record music and put advertisements in the local newspapers and national newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, Page wide and I think we could have something going going here.

John Gardner: Are you catching this? This guy walks right into the office of these white executives and says, Look, man, I’m going to save your business He’s from Chicago. He slick dressed. He same and I got connections. I know Bessie Smith, he said. I know Jelly Roll Morton and he says, I can get these guys. I can get them to record for you. I’m connected. I’m plugged in and he gets them to go for it. Now again, they’re not doing this hoping to preserve the culture. They’re not doing this because they want to document this great music. They’re just trying to spend a buck that’s as American as it gets. We own Mayo J. Williams a huge debt for having that bravery, for having that foresight. If it wasn’t for him, very likely there’s several artists that shaped the music as we know it, who never would have been heard. Now the more I started looking into this man, he was incredible. He was college educated from Brown University. He served in the Army in the first World War. He was a professional football player. He was actually one of just three African Americans in the first year. The NFL, so on top of being in the Grammy Music Hall of Fame, is in the NFL Hall of Fame. This guy was amazing when he said, “Yeah, I think we could get something going. I think I could save your record company.” He was not lying,

Alex Van Der Tuuk: and they started recording, in the late ‘22 early ‘23 with Alberta Hunter and Lanette More. Alberta hunter’s first recording was an instant hit. They sold like 5,000 copies off her first release, with 5,000 records sold. All of the sudden, they had something going

John Gardner: 1929 was an important year for a few reasons. Up until that point, Paramount’s largest selling artist was Blind Lemon Jefferson. That’s one of those bluesman original paintings that I picked up from the resale shop I told you about earlier in the episode. Now I couldn’t let that one go cause Blind Lemon Jefferson’s from Texas as am I, but also he changed the game. He was the first artist to make it big, just him and a guitar just moaning there was nothing like it, it was huge. 1929 is when we lost Blind Lemon Jefferson, he passed on. So Paramount is on the hunt, trying to find their new Blind Lemon Jefferson, who’s going to fill those shoes who can fill a room, be an entertainer, with just himself and a guitar. Blind Lemon Jefferson laid the groundwork for Paramount’s discovery of one of the most amazing and influential entertainers of all time, Charlie Patton.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: Charlie Patton is considered the Godfather of Blues, where Robert Johnson is the king of the blues. He’s is the Godfather of the Blues. He was a well known character in Mississippi, worked on a plantation Dockery Farms, world famous plantation, where the Blues was almost born, you would say. Anyway, in 1929 Patton was found, and he was sent in for his first recording session to Richmond, Indiana. That’s where they made that day long session with Charlie Patton, where his first recording came from Pony Blues and Benny Rooster Blues. Those are the cornerstones of any collection. Ask any collector of blues music.

John Gardner: Those aren’t just the cornerstone of music collections. That’s the cornerstone of American music as we know it. Okay, there’s- there’s nothing like it. Listen to recordings of Charlie. Find him on your own or go to WMFpodcast.org. listen to them there. Now as far as the recording quality they’re terrible. There’s pops and hisses, but through all that, you can hear just unbridled musicianship. What sets this apart from Swanee River and the things that had been recorded up until now, this man by himself sounded like an entire band. He’s shooting for the back row. He shooting beyond the back row of seats. He used to playing at Juke joints where he’s playing so loud between his legs behind his back. He’s drawn in people off the streets, off the fields to come listen to him!. They put a microphone in front of him and he just lets loose.

(Music)

So Paramount Records is at the top of the world right now, right? They’ve found someone who will eventually become the most influential artist who’s about birth. An entire music genre, the Delta Blues. What could go wrong? Well, the other reason that 1929 is an important year in the United States, that’s the beginning of The Great Depression.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: That period in Grafton was only a very short period, relatively speaking, from late 1929 up until mid 1932 and then boom all of a sudden depression was there, and they close the doors.

John Gardner: Just like that, It’s over. Now, they kept running the furniture company, but once they closed down operations for the Paramount Records section, they had little to no regard for what was left of their stockpile of records. They just didn’t care, proving once again, as they did throughout the entirety of their endeavors, they didn’t care at all about the music. They did nothing to preserve what they had. And yet again, this music was almost lost forever.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: Nobody heard from them again up until 1942 when they started selling out their metal masters.

John Gardner: Okay, so 10 years went by, but they started selling their mental masters. What collectors or something?

Alex Van Der Tuuk: For Ah, of course, War affairs.

John Gardner: Oh, come on!

Alex Van Der Tuuk: A long period of time there wasn’t enough interest in it because simply there wasn’t enough material left of that company. Everything had gone with paper drives and scrap drives enduring World War ll. So there were no recording ledgers, that were no metal masters.

John Gardner: Man, that’s heartbreaking. But Okay, that’s during the war what about before that? There was a period of time where they were just sitting there in a warehouse somewhere. Whatever happened to those records?

Alex Van Der Tuuk: I did speak to ah, former mayor of Port Washington, who ah, who as a kid stood on one of the buildings in Port Washington. That was the warehouse where older, paramount masters and records were stored after the the company closed in Grafton. And as a kid of 14 years old, he got a shotgun. He knew where those records were. So he, picked a pile of records and stepped up on the roof and sailed the records, and they shot him to pieces.

(Music)

Angie Mack Reilly: Oh, I remember going to one of the historical society’s one day said “Can I look for newspapers from this area 1929 to 1932. So she takes me back to this-this newspaper archive room and all these newspapers from 1929 to 1932 are missing.

John: You have to imagine that at a time that was so segregated, these black musicians had to come in through the back door and sneak out at night. There’s no way this white community was totally amped to have them coming through town in the first place, much less you know, they’re not going to put up the effort to preserving this music.

Angie Mack Reilly: So now we are at the Grafton House of Blues. (Laughes) Yeah, I like to pretend that they walked past my porch. I call it my Mississippi porch.

John Gardner: The voice you’re hearing there is Angie Mack Reilly. You heard her a little bit earlier, but she’s going to become very important to this story into the story of Paramount as a whole,

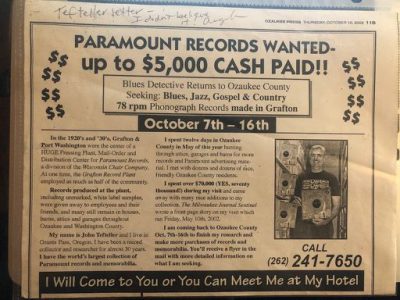

Angie Mack Reilly: So I’m self producing in this town house and got a piece of mail from a guy named John Tefteller. “Paramount Records wanted up to 5,000 cash paid. Blues detective returns to Ozaki County seeking Blues, Jazz, Gospel and Country, 78 RPM phonograph records made in Grafton.” You know, it says I pay in cash and you know, it just was this cheesy thing.

John Gardner: We actually have a photograph of what she saw in that newspaper over a WMFpodcast.org you can check it out over there. So it might have sounded cheesy, but that ad was super legit. And that man, John Tefteller. He’s at times paid upwards of $30,000 for one single record. Over the years, he and passionate collectors like him have unearth unimaginably rare records, sometimes finding just one single record of an artist or even a style of music, without which those sounds would’ve been lost forever. And in fact, if he never would have come to Grafton and looking for these old records, this Paramount history could have easily slipped away and almost certainly never would have gained recognition and Grafton in itself, because Angie may have never heard about it. But once she did, she took action.

Angie Mack Reilly: And I thought-There’s I thought I’m a musician. I had lived there for several years. I want to say at least five and I had never heard anything. And this is us you’ve seen it very small community. I look on the Internet, which was just developing at the time. Back in 2004 I couldn’t really find much of anything. So I go to the local library and asked them, “Do you? Do you know anything about this recording studio in Grafton? And they direct me to a book by Alex Van der Tuuk, who lived in the Netherlands.

John Gardner: That’s our Alex from the interview earlier in the episode.

Angie Mack Reilly: So I contacted him through email and said, Alex, I live in Grafton. We started to find everything and anything that we could about the artists about the employees, photographs, articles and started throwing them up on Paramount’s home.org because we knew people needed to be educated, and that’s how it began.

John Gardner: Humble beginnings. But Angie wasn’t satisfied with just a virtual commemoration of Paramount in its history all over the town. There’s evidence of her and Alex’s work and the team they put together. She took us on a walking tour and towering over a small, faded historical marker, which used to be the only thing that would designate the site has anything to do with Paramount History is a new, shiny, easy to read marker, which stands at the spot of where the recording company actually used to be.

Angie Mack Reilly: This is the Milwaukee River. After the Great Depression. They just dumped a bunch of the records into this river and that’s why history detectives. PBS history detectives came here.

John Gardner: There’s a link for that WMFpodcast,org, Of course. She took us also to the downtown area, and my eyes were immediately drawn to the names that we mentioned before: Charlie Patton, Blind Lemon, Jefferson, Skip James. They were all inscribed literally across the downtown and a design like Piano Key.

Angie Mack Reilly: There’s not even enough spaces, to name everybody who recorded here. The giant keyboard that you saw is called the Paramount Walk of Fame. So the whole area that downtown pays tribute, there’s also a sculpture, and it’s supposed to simulate Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey and Son House. For a sculpture with three black artist to be in the center of downtown Grafton is really a huge accomplishment.

John Gardner: Yeah, no joke, because Grafton and this whole Milwaukee area remains statistically the most segregated part of the United States. So big accomplishment, indeed. But Angie has been out here pretty much single-handedly working to preserve this history. It’s why she calls her house the Grafton House of Blues. But even for someone has dedicated and driven as Angie, it takes more people getting involved.

Angie Mack Reilly: We need more help. We need more funds. We need more people who are interested in this history to get on board and help because the locals are not going to do it. I think predominantly, it’s just indifference. It’s a matter of musical taste, and people in this area have a certain musical taste that doesn’t include the Delta Blues. But around the world there’s a huge, huge following of people who are very much into this music. They recognize that Delta Blues was the ripple in American music that affected Elvis Presley. It just goes on and on the effects that have come from the Delta Blues. They say Delta Blues is the roots, and everything else is the fruits. I’m worried about the history getting lost again.

John Garder: Man. It’s the same struggle, same as it ever was. But now at least thanks to Angie Mack Reilly and Alex Vander Took and others we have this downtown written in stone commemoration of Paramount. We have Alexa’s historical book, Paramount’s Rise and Fall, which has just recently been reissued, actually, and updated. You can find that at Agrim blues.com, But in addition, there’s been another really big important commemoration and restoration project of Paramount Records that was undertaken not too long ago.

Were you involved in the Third Man Records, Jack White box set?

Alex Van Der Tuuk: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I was executive producer on research historians. Well, the company of Jack White and Dean Blackwood’s of Revenant records. They approached me first in 2011, Dean Blackwood had a layout of a plan of recording as much paramount songs as a multi media box. And with that idea he went to Jack White and Dean said, “Well, we can’t do this project without Alex Van Der Tuuk he is the authority on the Paramount Records.” And so I got an email from from them and they said, “Well, we want you in. We want your book to be used as an under layer for the story, we are going to write for the books that will be involved. And we wanted to do two box sets within total 1,600 transfers of the Sony eight RPM records from this and on a USB drive flash drives and they go with their own build websites. There’s four books involved and it’s It’s an amazing book box set and it took us two years to get both box sets done.

John Gardner: Angie helped with that project as well.

Angie Mack Reilly: One day this huge giant semi shows up in front of my house. Some guy comes out and gives me the Paramount Box Set number one. I had no idea it was coming. Then the 2nd one somebody had dropped it off at my back door.

John Gardner: That’s great. And Angie’s showed us both box sets. They really are incredible. Both sets won Grammys, actually, but I can’t help but think Angie’s two copies are probably the only copies of that Paramount record collection for miles and miles in that area. It’s just not the music of the people that lived there, but it’s music of the world. It’s music that’s important, and it’s a perfect example of what we’re going to look into with this podcast. The podcast and our nonprofit is called the World Music Foundation, and we know that’s a pretty difficult term to pinned down. Next week we will have on this show, an interview with one of the men who invented the term World Music. You can actually pin it down to the exact date and even the exact bar where this term was created. So tune in for that next week. But I don’t want to leave this episode without making it very clear. Our definition of World Music includes music, of course, from every part of the world, so it’s not just other. It includes music of the United States like we looked at here in the blues, and it includes music of Europe just as easy as it includes India and Africa and Latin America, so we truly mean it is inclusive. It’s music from all over the world, and you probably notice that accent from Alex there at the beginning. He’s the world’s leading expert on this deep blues Paramount record label. That’s not a Mississippi accent.

Alex Van Der Tuuk: I was born and bred in the Netherlands have been here all my life. World music in my book is a very broad term that you can apply to all kinds of music. For example, you have Scottish Irish music, and that’s considered world music as well. More even into folk music were folklore, music, and in America you have the same sort of museum of music like jazz, for example, or blues or Zydeco music or Cajun music even. There’s all kinds of music that applied to that definition.

John Gardner: So how did you learn about and get involved with the history of Paramount Records? In particular?

Alex Van Der Tuuk: When I was 14 years, I was introduced to the music of the Rolling Stones. They influenced my youth so much. There was a song called Love in Vain on the Let It Bleed album done by Robert Johnson, originally in 1936 or seven. So I went to local record store, pulled the record by Robert Johnson from from the shelves and then and ask the man behind the desk could play it for me and Robert Johnson didn’t do it for me. And now he’s considered King of the Blues and it took me another 15 years before I got a really interesting in Blues music first through Elmore James from the fifties, Howling Wolf, Muddy Waters. And then that Ah, really, really got me. And I decided to go to the local library and see if there’s any history books on Blues music and lo and behold, there was a book called Sam Charters: The Country Blues from 1959 and I pulled that book and it was specified on the early record companies that recorded jazz and but specifically Blues music like Columbia records, Okeh records and there was Paramount.

John Gardner: So look, you never know when you might hear or learn about something that’s going to change the entire direction of your life. We in this podcast aimed to be that friend that you might not have that turn you on to things from every part of the globe, you will become that friend for others. Share what you learn here, share about the music, the people, the cultures that we expose you to. And let’s just get a broader world view going for ourselves for the people we know care about. And let’s just have fun doing it. By now, you should probably know our website. WMFpodcast.org. Always there will be extra information on there and links, definitions, photographs, much more information for the extra curious. You can go to WMFpodcast.org. Also you can shoot us a reply, shoot us a hello. Tell us what you’re liking. What you’re not liking about the direction we’re taking here at the beginning of this podcast. But most importantly, continued to listen widely. Open ears equals open minds. We’ll see you next time.

(Music fades)

For The Extra Curious

Musical Mentions

0:50 Muddy Waters

0:51 B.B King

0:54 Blind Lemon Jefferson

0:56 Charley Patton

0:57 Skip James

1:09 Blues

1:12 Africa

1:50 Skip James

2:03 Big Bill Broonzy

2:07 Bill Big Broonzy: The Man That Brought The Blues to Britain

2:14 Paramount Records

3:44 Jazz

3:55 Johann Sebastian Bach

3:55 Ludwig Van Beethoven

3:55 Johannes Brahms

3:59 Franz Joseph Haydn

3:59 Wenzel Müller

3:59 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

4:06 Vaudevillan Performers

4:08 Dixieland Jazz

4:10 Creole Music

4:14 Military Bands

4:49 Al Jolson

6:11 Pop music

6:19 Wisconsin Chair Company

6:28 Phonographs

7:21 Alex Van Der Tuuk

7:31 Paramount’s Rise and Fall

7:55 Classical Music (Western)

8:05 Vaudeville

8:10 Country Music

8:37 Mamie Smith

8:38 Crazy Blues

9:09 Race Records

10:10 J. Mayo “Ink” Williams

10:31 Blues Music

11:15 Bessie Smith

11:17 Jelly Roll Morton

12:31 Alberta Hunter

12:32 Monette Moore

12:53 Blind Lemon Jefferson

13:48 Charley Patton

13:52 Dockery Farms

13:57 Robert Johnson

14:29 Pony Blues

14:31 Banty Rooster Blues

15:10 Swanee River

15:21 Juke Joints

15:46 Delta Blues

16:59 Metal Masters

19:25 Grafton House of Blues

19:34 Angie Mack Reilly

19:56 Blues

19:56 Jazz

19:56 Country Music

22:43 PBS History Detective: Paramount Records Episode

22:59 Charley Patton

22:59 Skip James

22:59 Blind Lemon Jefferson

23:27 Louis Armstrong

23:27 Ma Rainey

23:27 Son House

24:28 Delta Blues

24:49 Elvis Presley

25:22 Paramount’s Rise and Fall

25:29 Agram Blues

25:41 Jack White Box Set

25:54 Dean Blackwood

25:55 Revenant Records

27:10 Paramount Box Set #1

27:28 Grammy Award

27:57 The World Music Foundation

28:05 World Music

29:10 Folklore Music

29:18 Zydeco

29:22 Cajun Music

29:36 Rolling Stones

29:41 Love in Vain

30:10 Elmore James

30:01 Howlin’ Wolf

30:04 Muddy Waters

30:28 The Country Blues, by Samuel Charters

30:40 Columbia Records

30:42 Okeh Records

30:43 Paramount Records