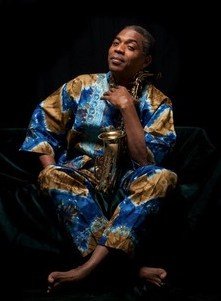

Femi Kuti

World Music Foundation Podcast | Season 1, Episode 13

“We have to see the beauty of Africa through the music.”

About this Episode

As a renowned Afrobeat and Jazz musician with four GRAMMY nominations, Femi Kuti is well-respected around the world for opening minds through the power of his music. John spoke with Femi from the Shrine in Lagos, Nigeria, where he shared the details of his musical upbringing and the importance of different music cultures. He also gets into his life-changing transition from the Saxophone to the Trumpet and the effect this has had on his music and his thoughts. Femi is the son of Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, and is considered a torch-bearer to his father’s legacy, but in this interview Femi explains why he believes that his mother, Remilekun Taylor, is actually 90% responsible for who he is.

Hello, hello and welcome again to the World Music Foundation podcast. I’m your host, John Gardner, and today we speak with Afrobeat icon and concerned citizen of the world, Femi Kuti. The World Music Foundation podcast is produced by the World Music Foundation. Our nonprofit mission is pretty simple: to open minds through music. Our guest today, Afro-beat legend Femi Kuti, is on that same mission. He explains in this interview that whenever he performs, his goal is to help the audience see Africa through his eyes; to see Africa through the music. He’s an ambassador, he’s a great one at that.

If you’re not familiar with the style of music called “Afrobeat”, no worries. That’s what we’re here for. We’re gonna discuss that and as always we’ll present music clips but we’re also gonna mention very briefly Femi Kuti’s father, Fela Kuti. Now, we don’t get deep into it in this episode because that’s a huge topic and frankly it’s discussed several places. You can find many interviews that focus on that. We get into areas that aren’t often discussed. For instance, you might be surprised to learn that Femi was much more influenced by his mother, who wasn’t famous at all and who’s hardly ever spoken about, than his enormously famous father. But you will hear his father, Fela Kuti, referenced throughout this interview. So, if you’re not familiar, we’ve provided a biography video at WMFPodcast.org/13. There are also seven or eight videos and photos of our guests at our website. There is also a full transcription of this interview, as with all of our interviews.

This interview was done via telephone while Mr.Kuti was at the New Africa Shrine in Lagos, Nigeria. You know, I could do a whole episode on what is the New Africa Shrine, what does it represent, what’s the history. But, I’m not gonna get into that. I want to get into the interview and also get into all the multiple GRAMMY nominations that our guest, Femi Kuti, has received. I can get into his worldwide tour schedule, even the fact that he holds a world record, but that can all be googled. And I’ll actually tell you more about that world record at the end of this episode. So, rather than me rehashing his awards and accolades, that you can find all over the internet, I wanna get you into the content that’s exclusive to the World Music Foundation podcast.

We’re gonna start with how Femi Kuti describes himself. Here is our interview with Femi Kuti.

(Interview Begins)

John Gardner: Hello, Hello. Thank you again for tuning in to the World Music Foundation podcast. I am your host, John Gardner, and today we have the great pleasure to speak with worldwide legend of Afrobeat music and concerned citizen of the world, Mr. Femi Kuti. We thank you so much for being here with us Mr. Kuti.

Femi Kuti: Thank you very much, Thank you.

John Gardner: So, we have listeners from all over the world and you’re clearly known worldwide, so most will probably know of you already, but how would you answer the question “Who is Femi Kuti”?

Femi Kuti: Wow. Musician, son of Fela Kuti, father himself, tries to be very simple in life and things like that.

John Gardner: Those are big words that you’ve used. Father, of course, is an enormous word, it means a lot. Another one is musician. A lot goes into that term. You’re a musician primarily known for performing Afrobeat.

Femi Kuti: Yep.

John Gardner: How would you describe Afrobeat to someone who’s never heard the music?

Femi Kuti: Oh, it’s a music that was formed by my father. It’s a mixture of Highlife African Traditional Music, and African Culture and Dance, and Jazz, and of course it’s own gift as well. Natural gift as a musician.

John Gardner: And these terms being mixed with Jazz and the African traditions, there’s another style of music called Afrobeats with an “S” on the end. Is there a relation between the two styles?

Femi Kuti: I think it’s because most of the young artists playing Afrobeats have taken a lot of samples from the Afrobeat. And I think they came up with that name because they are hugely influenced by my Father.

John Gardner: And by you as well I’ll add, right?

Femi Kuti: Yes, I did not- I try not to- I try to be modest.

John Gardner: Yes, but while you speak modestly, you’ve been making very bold music for- for decades and you’ve influenced so many around the world.

Femi Kuti: Thank you.

John Gardner: With your touring, as a torchbearer, as the foremost representative of Afro-beat around the world, have you seen the reception differently from parts of the world? Are there places that respect Afro-beat more than others? Or that you get better receptions in different parts of the world?

Femi Kuti: I wouldn’t say so, because you, over the years I’ve been to places that probably never heard of my father at the beginning and, or they’d not heard of me. And after the nights, it, it changes. So, I’ve never played a gig thinking, “oh, they don’t know the afro-beat, or me.” I took every gig as important as the next one. I put as much energy and, because you never know who’s in the audience. You never know who you are playing to, or who’s inspired. And so I’ve never looked at any territory saying, “oh, this is more, we have more fans.” It’s my kind of mission that even if we don’t have fans we see as many people, so playing festivals where we are not known, very important clubs where, towns we are not known. It’s as important as playing where we’re highly respectable known. And most easily I could speak to cities like Washington, San Francisco, Paris, London, I mean of course big cities are already acclimatized to the afrobeats, but I would not say they are more important than any other small town, or village or city. It is very important for me to respect all audiences, and all peoples.

John Garder: You clearly take the role of musician and music creator very seriously. Could you take us back to early days? I’m interested actually, do you remember the first time you experienced music outside of your own culture?

Femi Kuti: Outside my culture? Probably. Yes, probably just The Beatles probably. I believe I was seven or eight then. My mother had the album. I can’t remember the track, but every time I hear that track, I don’t remember the name. Every time I hear it it takes me back to the sixties. We just had the, we just bought the record player, and that was probably the only record we even had. I think it was my mother’s. And we’d listen to this. This is probably- apart from the Highlife in town, my father played rehearsal with the band at home, this was the first time I heard something completely different. And we kind of wore- it was rare that we had two records- we wore it out playing it.

John Gardner: Do you believe that hearing music from a different culture brings you any close- like when you first heard the Beatles, did they give you any impression of the culture that you were hearing? Of different people at all?

Femi Kuti: I would say, I love the music. No doubt. I think it was more- I thought it was popular at its time, and we were very, life was kind of difficult, so there was a kind of freshness definitely. If I recollect properly. I didn’t know it was the Beatles, not for years. I do not read too much significance of making a difference. It was just, oh we have the album, play the album and basically that was it.

John Gardner: How do you think now of people hearing your music? Do you feel that they can get a little sense of where you’re coming from? Do you feel that when you perform for other cultures, it can help them understand Nigeria and Africa?

Femi Kuti: It’s one of the main objectives of performing. Live, especially. We have to see Africa through my eyes. We have to see the beauty of Africa through the music. We have to see that giving the opportunity to africa to excel beyond a reasonable doubt, and understand Africa is going through what it is going through because of slavery, because of bad governments, corrupt African governments, because of colonizing, and I think we see all this through the beauty of the music. And, most importantly, world peace. That we all, amongst us, and be on the planet, and it is very important for us to live together. It’s like all trying to stay in your house. Or, we make the house beautiful and nice. And we see that everywhere in that house, the corridors, must be kept clean, and nice and good. So, whatever happens in America affects me in Africa. What happens in Africa affects people in Tokyo, in Japan, in Australia. We all have to be concerned with one another. We have to live like brothers and sisters, and we have to understand that segregation or racism has no place in this world. And if it is a very uneducated or kind of primitive mind that will have this kind of thought. It’s very important for us to move the world forward and give the children a beautiful future. So, it is all this I try to do with my music.

John Gardner: Yes. And as your track in your album says, “One People, One World,” right?

Femi Kuti: Yes.

John Gardner: So many people know about your father, obviously there’s been books, there’s been movies, broadway musicals, plays, statues. I’m wondering, is there anything that you’d like us to know about your mother, Remi Ransome-Kuti?

Femi Kuti: Wow. She wasn’t known in public as such. She was very powerful. I think I owe her ninety percent of what I am today, because she held the home. She, my father wasn’t a conventional father, and she had to explain to us why he wasn’t around. She explained to us stardom, because stardom in Nigeria, you could say, was new. It was the first time in Nigeria that any artist was that huge. Look, with my father, I mean growing up we, now we’re starting to understand and forgive him for not being the father we wanted him to be. And this is because of my mother. She is, she is the perfect mother who made me, the children, not see any wrong in our father and just love him, what he is. So, I could forgive him and once, when we inherited all this money from his back catalog. It stead of buying cars and building a home. We built the Shrine in his honor. And we have the biggest festival in Nigeria now, the Felabration festival, which is global now, celebrated worldwide. This is because my other sister and myself find it very important to preserve his legacy, understand his legacy and see him for, basically, what’s he was in his life. A fighter, a revolutionary and then, I mean, I mean, I remember the first time he was in prison. We cried, because to go to prison, you have to be a criminal. And again, my mother was there, “Oh no, no. You’re father is being victimized because of “blah, blah”. She would take time out to explain our father, and then, when can you understand again, for instance, the importance of why I wanted to play music because again I said my father wasn’t conventional. So I never went to school. He was brought to school by his father. And through my mother, I understood again, Wow! Because I didn’t have the opportunities to have a good education, and I can’t read or write music I will have to work ten times harder than any other musician. I said, “ need to find my own voice, find my own music, my instrument and things like this. So I picked up the sax. taught myself the sax, taught myself the trumpet, and this. I think this has to do again with the upbringing from my mother. So I owe her, but very few people know her in public. There are very few photos. She was like a hermit. She didn’t like the public eye on her at all; she avoided it completely.

John Gardner: Well, if you’re okay with it, we’d like to put a photo of for this episode of your interview at WMFpodcast.org/13. We’d like to put a photo of your mother and description. We appreciate you speaking about her. It definitely sounds like she had to have a strong role to give you perspective on the kind of life you were living.

Femi Kuti: Yeah.

John Gardner: You mentioned teaching yourself, being self-taught.You come from a musical family, why were you self-taught? Your father didn’t teach you? No one else passed down that kind of knowledge? You didn’t go to music school?

Femi Kuti: No, because my mother wanted me to go to England to school and he wanted me to go to Ghana, so I ended up going nowhere. Because he was band leader at that time, his family marched out teaching me. My Mother got very angry that- “Why would you not give your son the kind education your father gave you? So, I had to stop lessons two weeks. So, I got no lessons. So I picked up, I still had no Saxophone teacher. I tried to teach myself, how to hold the saxophone and blah, blah, blah. And, I really was so bad because I had no teacher. So, later I joined my father’s band, and it was by being in the band that, I’d sit up there watching him, listening. So, I learned basically like this. Unfortunately for me, there are a lot of die-hard fans around my father who thought I was the greatest thing on earth, and he kind of misled me. Putting wrong ideas into my head. “Oh you are the greatest saxophonist!” And I was actually a load of rubbish. When my father got locked up, wrongfully, by the present administration, then he was a military man. The military of Muhammadu Buhari. I moved back to my mother’s house. And my, my maternal grandmother came up to me and says, “What kind of lousy musician are you? You have been here for three, four weeks now and you have not even picked up your sax. And she gave me the blasting of my life. This completely changed my, I mean I cried all night. You know I was so arrogant, Fela’s son, coming from Kalakuta, nobody can speak to me like this! I’m. She gave me the talking you won’t believe. She really spoke to me. But this was what completely changed me. I was so ashamed to pick up my horn the next day, but I couldn’t even hear her. When I picked it up I could hear her, because she’s very british. I could hear like, yes I’ve given him a piece of my mind. No, I’m talking so badly, but it was this talk that really made me understand the gravity of where I was and what I have to do. So you see, my matrnal side, my mother and her mother, I owe so much because if that talk didn’t happen I probably would have been so arrogant, and very much concern about things I should be. I think I would have been more, people forcing me to be what I did not fully want to be.

John Gardner: Yeah.

Femi Kuti: This way I can find my own soul, my own self. And I knew I could never be my father. I didn’t want to be my father, I love my father for what he was, but I wanted to be me. So with this I had to search for myself. I use this technique in jazz as well, I knew I could never be Charlie Parker. So why try to be Charlie Parker, because I’ll never be Charlie Parker.

John Gardner: Yeah. Do you remember the first time you heard Charlie Parker?

Femi Kuti: Yes. It sounded so bitter; I hated it. My father was like, “You have to love jazz.” I said ‘No I can’t stand jazz, I hate jazz.’ He introduced me to James Moody. The track was, I’ll never forget, Moody’s Mood for Love (saxophone imitation). I went to Florida, a girlfriend of mine invited me to America for the first time. I got there, I go to the music shop, I said where is Moody’s Mood for Love and the guy says ‘oh we have one by…this guitarist,

John Gardner: Charlie Parker?

Femi Kuti: Great guitarist, George Benson. I said, “Wow, George Benson! He did “Mood for Love.” I was so excited, wow so funky, yeah. So I bought that. But then, for my father I bought “Mood for Love” as well. I bring them back, talk to my father about it. George Benson. I said, ‘Yeah see what I got,” then he said, “Are you so stupid don’t you think I know who that is? I told you buy something, you buy something else.” I got so angry I thought I was bringing something new to the home you know. So I went back and tried to get acclimatize to Moody’s Mood and I said, “Wow not bad,” I tried to play the tune, the first track (saxophone imitation). So I start to understand and went back to Charlie Parker and I (saxophone imitation), and I was like “WOW! WHOA! I’m in trouble!” Ah, the dexterity, the improvisation! And I said oh no I’m dead, I’m dead. Then I start to appreciate jazz. Then Dizzy Gillespie, Coltrane. I said Whoa! Art Tatum, I said Whoa! I went crazy listening to Jazz. Whoa! They were fantastic, awesome players, and I was like, “Wow, I will never be able to play like this.” And this worried me like all my life, man. It worried me. I knew I could not beat them. And I moved back again, it was my grandmother when talking to me I would say, “Look I can’t be like these people, I can’t even be like my father.” Why don’t I find myself? And that’s where the search for Femi Kuti started.”

Hours and hours, like twelve hours a day. I had to look for a fine tone on my saxophone. I remember once, even undoing my saxophone completely; I took it apart. Just perhaps saying, “to play the saxophone, you must learn to repair the saxophone.” So I took everything apart. I said, “Wow, how foolish can one get?” I didn’t know how to put it back. I had an airsax, and had to put it back together. All the pieces were there, and my hands were sore. This was the kind of crazy things I would do to find myself. I come up with a brilliant idea okay put the sax apart if you are a saxophonist. I would just do that. I did so many things like this. All that led to Femi Kuti today.

John Gardner: Yeah. Maybe you couldn’t put the sax back together, but you sure could play that sax after 12 hours day after day all this practice. How did you decide, and what was it like going back to the basics after so much time on saxophone, you decided to go back and learn trumpet right, why?

Femi Kuti: I picked up the soprano sax because I wanted to play the trumpet. I was too ashamed to go back to the trumpet, because that was my first instrument. My father gave it to me, but I had no teacher. He had a cousin named Okolawo (sp?), who taught me the scale of C major. Now again I had a problem. I wanted to clean the trumpet, but you have to take out the valves, but I took them out wrongly, and I couldn’t blow it again, and nobody was there to tell me what to do, so I broke the trumpet, so I never played the trumpet anymore.

Then my son picked it up at three, and he inspired me and I said, “Wow, why don’t I just go back?” So I picked it up again, and my musicians, this was in 2000 we were recording the album ‘Fight to Win”. My horn players were so troublesome in the studio I said, “Wow, I’m putting this into practice now. You know I am such a determined person that, even if it kills me, if I say this is what I am going to do, I just end up doing it. It’s been now 19 years, and I think I am on the high range of becoming a very nice player. Trumpet’s again becoming my favorite instrument. I picked it up more because I was having a lot of problems. My mother, of course my father passed, my little sister followed him. It was a horrible part of my life. And building the shrine, we had the government descending on us. There is no social media of sorts, and the people were writing very negative stories about me, and this was a very terrible time in my life. I wanted something again to be more militant. I thought the trumpet felt like an uzi. I said, “Wow, I’m going to pick up this trumpet and I am going to kill everybody with the trumpet.” Everybody started laughing at me because these were my thoughts right?

John Gardner: Yeah

Femi Kuti: You’ll never, you are too old to learn the trumpet, you’ll never play the trumpet. Blah, blah, blah. So again, I just put hours, and hours, and hours, and hours and hours on the trumpet.

John Gardner: Wow, and did it make you more militant?

Femi Kuti: No, what it did was it took me to a level that I first protested against because I didn’t want to be cool, but it took me to a different kind of understanding of life, where there was so much peace.

John Gardner: Wow.

Femi Kuti: And because I wanted to go, I wasn’t violent, but hard; I was angry. I wanted to be more angry because of negative things coming in the paper that was happening in Nigeria at that time. I thought when we put up the shrine people would be happy at the time, and the people assumed so much negative things about me. And I’m the kind of person I was at that time it affected me very badly. So I wanted something to like, “F you all of you.” I was like exorcising. At the time. It took me somewhere, and I was like no I don’t want to go there! I tried, but it’s like the current, it’s just pulling me. It took me so far I couldn’t go back to where I wanted. And now I understand it’s for a reason. I started to understand so many issues around me. I never got angry anymore. The more I practiced, the more I saw how difficult it was to become a good musician. The more I realized how I was solving problems at home, or around the shrine. I’d just be calm in the mind, and the trumpet did all this for me.

John Gardner: That’s Amazing!

Femi Kuti: I was shocked, and I said, “Wow,” and I started to embrace this new me with the trumpet. Now people just see me and say, “why are you so cool?” With the trumpet all that aggression stopped, and I started to even understand the politics of Africa. While I had been hardcore saying this is the way to go, I said, “No!” You have always to look at things from a medical perspective. Why is it like this, somebody doesn’t just come to the doctor and say I am sick, and you administer any treatment. You have to find why is this person sick, what is the cause of this illness, before you administer any drug. It was the same way I looked at Africa. Why is Africa like this? We can say all what we like. Whether we like it there is a history to Africa. There is slavery, there is colonialism, there is the African government. So you don’t expect Africa with five hundred years of turmoil to just come out in ten years in twenty years it’s impossible. The way you understand it, you have to understand the gravity of what happened to Africa. Now Africa is taking over all over the world. Another important factor is many of us don’t even think, dream in our languages. Already this is our soul has been taking from us.

John Gardner: Yeah

Femi Kuti: When we understand this fact again. You see, so we have to understand what happened, why we are where we are, how to get out of there. What we have been made to adopt. To now be what we truly want to be. It is going to take God knows how long. In doing this we must not fall victim, and get angry, and start to blame for instance a young American boy and say “You took me as a slave”, because there is no fact to prove the connection to that stance that this boy was one of the players of slavery. So objectively we have to use our common sense. Now the world as I see it we are at the point where we all need medicine. We need technology, we are not here to make enemies with people, who, enough of them, do care. Why do you go to slavery again? It’s not like all of Europe was in favor of slavery. There was a lot of propaganda to support slavery. When we understand what the kings and queens were doing to the population then you understand why they were fooled by “yes, this is the way to go.” At that point in time of the history of this world. The trumpet made me go deep into thought. Finding answers and understanding the way forward.

John Gardner: I have literally have chills right now, the hairs on my arms are standing up. That this much insight, this much change could come from your dedication, your learning a new instrument, the trumpet. I could talk with you all day if I was able. I want to be respectful of your time. I wanted to talk about the shrine, I wanted to talk about Made, about your son. There were so many things I wanted to touch on, maybe will get a chance in the future, but in respect of your time I’m just going to transition into a lightning round if you don’t mind, and I’ll just ask…

Femi Kuti: Yes of course

John Gardner: Just four questions, no time for long answers, just quick answers. Femi Kuti what is your favorite food?

Femi Kuti: Food? I eat anything, nothing is my favorite food. Anything. It depends on how hungry I am, I’ll eat anything.

John Gardner: Outside of music, do you have any hobbies outside of music?

Femi Kuti: No. Just practicing.

John Gardner: Alright. There it is.

Femi Kuti: I love to go swimming with my children, but I just find more peace practicing.

John Gardner: Wow. What’s been on your mind lately?

Femi Kuti: Practice! Next album, how far I can take my music to, what more I can do to fascinate me and make people go like, “@ow!” And at the end of my lifetime will I be satisfied that I put all my efforts into producing the best I could, and don’t give myself any excuses on my death bed saying, “Oh I wish I had done this or that.”

John Gardner: Wow. I guarantee you make millions of people say wow with your music so, you’re in the right direction. The last question it’s kind of a complicated question, let me know if it’s not clear. If you can ask the universe just one question, and know the entire complete answer to that one question, what would your one question be?

Femi Kuti: I don’t think I would ask any question because I understand my being. I understand I am just human, and it’s not for me to question the universe. I think, When we play God is when we get into trouble. So I wouldn’t ask any question. I would just find answers for every predicament I find myself in, and try to solve those problems. I think as human beings we are here to, I think that life is a school we are here to learn.

John Gardner: Wow.

Femi Kuti: And nobody knows what comes after this. I think it is important to learn, history teaches us it’s best to live on the right path, be as good as possible in your life, and because we know that evil doesn’t pay. And so, I try to live my life like this. It’s not for me to question why the seas are there, or why we have to breathe, or I mean these are facts of life.

John Gardner: Wow.

Femi Kuti: It’s not for me to question why we must die, why we are alive. We are just humans.

John Gardner: Femi Kuti why, why do you have to blow my mind all the way up to the very end. It’s been such a great conversation with you. Hopefully we get a chance to speak again, I have on my personal bucket list to hear you live one day at the shrine.

Femi Kuti: I pray it comes true.

John Gardner: Thank you so much. I appreciate your time. Please pass all my thank yous to your team, and I really hope we will speak again.

Femi Kuti: Thank you. Have a good day.

John Gardner: Likewise. Bye.

(Outro Music Plays)

OUTRO:

John Gardner: Yeeees, yes, yes! Woo! Loved it. Can you believe that? He didn’t even want to ask a question to the Universe, he’s like “I’ll just figure it out, that’s our role.” He’ll just figure it out. Man, the man does not take the easy route.

As further proof of that, I mentioned at the top of this episode that I’d tell you about his world record a little bit. So, I always thought, and you might have heard this before, there’s a record that I thought was held by Kenny G. Even just recently, I don’t know how it came up in conversation but someone mentioned Kenny G. and I mentioned, ya know, world record holder. He’s amazing at what he does on the saxophone and I thought Kenny G. held the world record for the world’s longest note held on the saxophone. He held one note on the saxophone for 45 minutes, that’s incredible! It requires circular breathing, most importantly it requires incredible strength of mind and lungs. Just such determination. Well, I found out Femi Kuti’s blown out that record twice. He’s surpassed that in one attempt and then, I think he went to 46 minutes, but the next morning found out there was a gentleman named Von Burchfield, who had actually surpassed that Kenny G. record going all the way to 47 minutes and 5 seconds. Well he was heartbroken of course, he didn’t know if he could do it, if he could surpass that again, could get up the mental fortitude. But, he did. He set a date, went out to the shrine and I think, after seeing the video, I think not only did he break the world record for the longest note on the saxophone, I think he broke the world record for the most awesome party as you break a world record because he’s playing that one note and he’s got the dancers going behind him and people are fanning him right at the end and he succeeds and the whole place goes crazy. It’s pretty awesome.

So, actually, I enjoyed that video so much I’m going to pay now for you in its entirety the 51 minutes and 33 seconds of the longest note ever played continuously on saxophone. Here it is.

Video starts to play

Video stops

John Gardner: Okay fine, I guess you had to be there. Laughs. Did you think I was gonna play the whole thing? Did you check the time remaining on this episode? Ah, anyway. Amazing feat, wanted to bring that up to y’all.

Next week our episode takes us to Cuba. We speak with GRAMMY nominated, Havana-born pianist, composer and bandleader, Roberto Fonseca, about his latest album, Yesun, that came out just a handful of days ago. Here’s a little preview.

Preview begins

John Gardner: Clave, that’s actually the- the title of the last track of your new album.

Robert Fonseca: Yeah.

John Gardner: What is clave?

Robert Fonseca: Clave is a pattern. It’s like uh the walking line of the bass on blues or swing. The thing is very important. For us, that for us is really simple because that’s- that’s like the way you walk. The speed of the clave, that’s the way you walk. And the percussion rhythms, that’s the beat of your heart. And- and the bass line and the harmony, that’s your spirit. That’s the way you feel in your body, the health of your body.

Preview ends

John Gardner: We hope you’ll join us next week for that conversation. But for this weeks episode, we’re all wrapped up. Can’t thank this week’s guest, Femi Kuti, enough. Love speaking with him. Thank you to the Chocolate City Group in Nigeria for making this possible. Hope you know by now of our website WMFPodcast.org. Have you been there yet? If you have, let us know about it, let us know what you think. To get to this exact episode’s webpage, go to WMFPodcast.org/13. While you’re there, don’t forget to subscribe. You can do that through your podcast players but there’s several links on our website as well that you can subscribe through there.

Until next week, remember to listen widely. Open ears equals open minds. We’ll catch you next time.

For The Extra Curious

ABOUT OUR GUEST

Femi Kuti was born Olufela Olufemi Anikulapo Kuti on June 16, 1962 in London and he grew up in Lagos, Nigeria. He is the eldest son of afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti & Remilekun Taylor, and a grandchild of a political campaigner, women’s rights activist and traditional aristocrat Funmilayo Ransome Kuti. Femi’s musical career started at 15 when he began playing in his father’s band, Egypt 80 in 1979. On December 13, 1986, Femi started his own band, Positive Force, and was joined by his sisters Yeni and Sola (as the lead dancers) and began establishing himself as an artist independent of his father’s massive legacy. In 2001 he collaborated with Common and Mos Def on Fight to Win, and started touring the United States with Jane’s Addiction. After a 4-year absence due to personal setbacks, he re-emerged in 2008 with Day by Day and Africa for Africa in 2010, for which he received two Grammy nominations. In 2012 he was both inducted into the Headies Hall of Fame (the most prestigious music awards in Nigeria) and was the opening act on the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ European Tour, and became an Ambassador for Amnesty International. He continues to expand the diversity of his artistry on his 2013 album No Place for My Dream (another Grammy nominations) and his latest album One People One World. Like his father, Femi has shown a strong commitment to social and political causes throughout his career and continues to fight for a free and fair Nigeria.

Musical Mentions

0:08 World Music Foundation Podcast

0:11 John Gardner

0:14 Afrobeat

00:15 Femi Kuti

0:31 The World Music Foundation

0:52 Africa

1:23 Fela Kuti

2:20 New Afrika Shrine

2:23 Lagos, Nigeria

2:47 GRAMMY Awards

4:27 Highlife African Traditional Music

4:28 African Culture and Dance

4:32 Jazz

5:00 Afrobeats

8:08 The Beatles

8:35 Highlife

10:05 Nigeria

11:07 America

11:10 Tokyo, Japan

11:12 Australia

11:50 One People One World

12:17 Remilekun Taylor

12:39 Stardom

16:00 Music School

16:08 England

16:10 Ghana

16:38 Saxophone

19:03 Charlie Parker

19:26 James Moody

19:40 Music Shop

19:45 Mood for Love

19:49 Guitarist

19:53 George Benson

20:45 Dexterity

20:46 Improvisation

20:54 Dizzy Gillespie

20:55 John Coltrane

20:56 Art Tatum

22:52 Trumpet

22:58 Soprano Sax

23:01 C Major

23:21 Fight to Win

28:36 Made Kuti

36:08 Cuba

36:11 Pianist

36:12 Composer

36:14 Band Leader

36:15 Roberto Fonseca

36:16 Yesun

36:49 Clave

37:22 Chocolate City Group